All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

You'll Be Free Child Once You Have Died

The last time I saw my mother, her piercing image reflected back at me in the mirror of a rest stop forty miles south of Louisville. Outside, the sun sat low in the sky, blanketing the land with a fiery dusk. Inside, the reddish glow poured in through a broken pane of glass, illuminating the grimy tile floor. A cool autumn wind flowed in through the cracks in the window, scattering used wads of paper towels into a corner. Every minute or so the dim bulb flickered once, twice, and then completely out.

With a rolled up dollar bill clutched in an unsteady hand, I leaned over the sink, snorting first one line, then another, relishing the rush the white powder awarded. I rose up, swiping a hand over my nose and blinking back tears. Splashing myself with rusty brown tap water, I leaned forward until my head touched the cool glass.

She appeared between the next set of flickers, alabaster skin bathed in the light of a dying sun. With a rickety gait, she approached slowly, cautiously. The tentative steps of a toddler. She wore a short, mint green hospital gown that remained untouched by the breeze. The blackish brown of dried blood was spattered across her thighs, and small, solidified rivulets descended until they were almost to her knees. Her once youthful skin, now flushed and swollen, a sovereign beauty erased by a complicated birth.

Sweat glistened on her face, matting wisps of hair to her forehead. I gripped the sides of the sink, understanding this must have been how she looked in the midst of death; giving birth to a daughter she’d never hold. Breathing deeply, I felt nauseous by the sight of her, not so much afraid as ill, though her presence was worrisome at best. It meant that despite the fact that I’d stopped dropping acid weeks ago, I was still experiencing hallucinations.

Last month, I experienced three separate, obscenely graphic hallucinations, all involving the mother I’d never known. The only difference being the hazy, surreal quality present in the first three. Now, however, she seemed as real as anything in this abysmal, concrete outhouse. What once seemed like the result of too much acid was apparently something different, possibly a mental condition. Turning around to face her proved to be a feat unto itself. Seeing her reflection lessened her existence; it made her a simple illusion, a trick of the light.

But, even I wasn’t foolish enough or loaded enough to believe that. Two lines of coke do not equal phantom specters. Surrendering to my fear, I turned and noticed another difference between this vision and the previous ones.

She carried a large, leather-bound scrapbook, a book I’d know anywhere. This particular scrapbook had lain on the coffee table in my grandmother’s home from the time I’d been born until now. The cover was the faded brown of dying bark and felt rough to the touch. Sunlight reflected off the gilded edges, making it appear incandescent. The book lay cradled in her arms, heavy with sepia photos and yellow newspaper clippings.

She reached out, offering the book as if she were handing over a child, and placed it in my hands. Reluctantly, I accepted, and opened the cover, hearing the creak of the aged binding. I flipped for pages and pages, recalling certain photos with fondness, such as my fifth birthday party and Christmas of ’97. But the more I flipped, the fewer photos there were. More pages were filled with obituaries and death certificates than happy memories. And by the time I reached the last page, I found what she’d meant for me to see.

On the left-hand page, a newspaper article was held down with scotch tape, the headline reading, ‘Rest Stop Death Caused by Overdose’. I skimmed the page, noticing my name, but barely comprehending what I read. The date on the paper was two days from now. At least, that’s what I thought. The more I tried to remember, the less I could recall. What became especially hard to grasp was why I was in the rest stop to begin with. I’d stopped here what seemed like hours ago, but only moments before I had been…What had I been doing? Using the bathroom? Maybe that was it. I’d stopped here for a reason I could no longer remember. That seemed even more frightening than the scrapbook, not to mention the ghost of my long-dead, frighteningly corporeal mother.

The scrapbook began to grow ethereal and melt away, until I could see my hands through the cream colored pages. As soon as the book had disappeared completely, my mother grasped my hand and led me out of the rest stop and into the twilight.

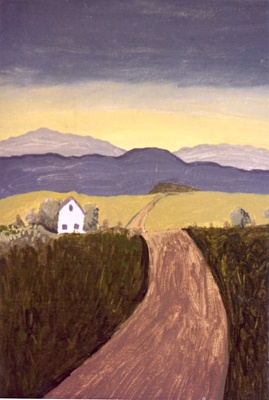

Looking skyward, I realized that the clouds no longer inched by slowly, they’d ceased moving completely. My death had carried me to a place where time no longer existed or mattered. She led me into a dirt path, a back road if there ever was one. I turned to look back at the rest stop, but it had disappeared as well. I noticed what an out of the way this was. What had I been thinking, stopping in the middle of nowhere? It’s a wonder my body was discovered at all.

She squeezed my hand, seeking my attention. With one thin, lucid finger, she pointed towards the road ahead of me, my path into the horizon. She became increasingly more illusory until, like the scrapbook and the rest stop, she too was gone. The path was mine to walk, the journey I had to conquer alone. Instead of feeling abandoned by my mother once again, I felt comforted by her ubiquity.

Taking one more useless breath, I steeled myself for the long walk and stepped forward into the dusk.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.