All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

The Story of a War Widow

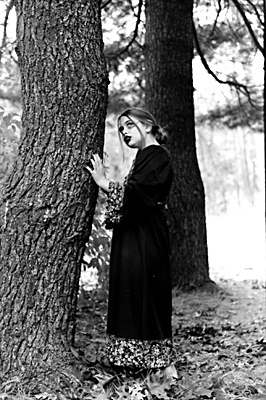

In the place where her eyes should have been were two big black almonds. She wore so much makeup that her actual eyes were just slits, especially in the bright sunlight. The eyebrows above were the sharpest I had ever seen, as if they had been drawn with a ruler. Her lips were cleanly outlined and coloured in red, though the shade had a surprising undertone of electric pink. The rest of her angular face was a smooth, satiny ivory that left no shadows or particularly noticeable features except those deliberately emphasized. Her hair framed her face and was just one tone lighter than the almond shapes. It was wavy and luscious, looking at once both flowing and firm. It swayed softly with the breeze, in one piece, not a single hair wafting free. I guessed that she was thirty-four, the perfect age for a female as it allows for sophistication without her showing the effects of age in excess.

She surveyed the bus from tip to tail, pursed her lips and came forward. I understood her reaction. This was a nice ride for me, but she did not look the type to travel by this sort of transport. She was the only person at the bus stop so we lurched off as soon as she was aboard. She staggered a little and her heels tapped loudly, above the hum of the engine. She moved forward with stiff legs and slipped into a seat two rows ahead of me.

Even with such a poor view of her as I had, she was hard not to look at. But other things were on my mind. My eyes went to the window instead. We drifted through the outskirts of the Daddesque town and into the country. I didn’t see the houses or the trees or the blue-grey sky. My eyes blurred. I knotted my eyebrows tight until I simply had to fish out a handkerchief. When I was tidy once more, I glanced around to see if anyone had noticed and caught the woman looking at me. She didn’t pull away immediately. She narrowed her eyes (it would have been hard to tell, but the slit of white and pale blue disappeared for a moment). Then she turned slowly back to face the front.

I moved my handbag to the side closest to the window and tried to hide the handkerchief in my hand. I sighed. It was too hot for my jacket but it was the only dark one I had. It wasn’t really mine; I had found it in my uncle’s wardrobe and altered it to fit. I looked at the woman two rows ahead. She was fidgeting. She tried to lean against the window but there wasn’t much of a ledge. She shuffled closer to the aisle. She put her hands on the back of the empty seat in front. She crossed her arms. She tried to cross her legs but we turned a corner and she almost toppled right off the seat. She looked up to the top of the bus and then back to the end of the bus. She seemed to searching for something. Her eyes examined each passenger, passing by some quickly and lingering on others. She never stopped long enough for the person to notice. That is, until she looked at me.

The corners of her lips twitched as she saw me. I was too inquisitive to switch my gaze. I watched as she picked up her handbag and moved right to the edge of the seat. Then, I suppose when she had ascertained that the bus was going at a steady pace, she swooped upwards. She moved rapidly backwards and dropped herself into the seat across the aisle from me.

She smiled demurely and said, “Hello.”

“Hello,” I said, trying to smother my confusion with politeness. As I went to look away, she quickly slipped a statement in that was obviously meant to be a prelude to conversation:

“I must say, I haven’t seen any young person looking as sad as you do since the end of Market Garden.”

I blinked at this peculiar offhand remark and sat dumbly for a moment too long, prompting her to say, “Perhaps you’re going down to London to meet with some other young people and have a party. I do hope you cheer up by then or else it will be quite a dreary affair.”

I started to explain that this was not the reason when she said, “The young people in town have been going down to London for parties with friends. I told them that they should simply get together and have a party in town like the children have been doing but they wouldn’t have it.”

“Oh,” was all I could say.

“Which town are you from, then?”

I paused to see if she would allow me time to answer and when it seemed she would, I said, “I’m not actually from a town nearby. I have been living in the country with an aunt. I’m going back home just now.”

“You live in London! What’s there to be sad about? Are you working as a secretary? Or have you got a boyfriend you’re going to?”

“Neither,” I said curtly. “I am going back to my parents’ home in Croydon.”

“Are you travelling that far alone? Was there no relative willing to accompany you? No friend? No”—and here she smirked a little—“gentleman?”

I took a deep breath, wrung my handkerchief in my hands and said, “No, there was not.”

The woman stopped in her excitement and paused with her mouth open for a few moments. She then abruptly shut it and folded her hands on her lap. When she proceeded she spoke with much more caution and sensitivity, “Are you”—she eyed my dark attire—“in mourning? You’re a war widow, perhaps?”

“No, I suppose, I cannot call myself quite that,” I said. There didn’t really seem to be an appropriate term for what I was, and when one cannot exactly define their suffering it does tend to leave a sort of disappointment. I felt a little empty.

“But you did lose someone... in the war, was it?” I nodded and she looked understanding. “I lost my husband. Who, if you don’t mind my asking, did you lose?” She leaned towards me, with a gentle smile.

I hesitated at first, and then I said, “It’s a rather long story.”

“This is a rather long journey. And I don’t see myself finding any other pleasant company on here.” She looked at a trio of giggling platinum blondes at the front of the bus and we shared a sneer.

“How about I give you a condensed version?” I suggested.

She shook her head. “This isn’t soup! A heart can’t feel without a whole.”

I hesitated and then thought, “What harm can it do?”

When I agreed she smiled even more and took a quick chance, jumping from the seat across the aisle to my seat. She gave a high laugh when she got down safely and then she got comfortable. I moved closer to the window, slightly bemused by her boldness. I got a close-up view of her now she was right beside me, but I felt uneasy because she had the same advantage. She looked at me with encouragement, and if I had to tell somebody my story it might as well be someone who had suffered something similar.

“I did lose someone,” I said. “It was someone very dear to me. He was... a childhood friend.”

“Was this from your childhood in Croydon?”

“Yes. His parents had this nice house there, just a little bigger than mine. Our fathers did business together sometimes. Our mothers didn’t really get on; his was a high society type and mine was a bake sale type. We had fun together, though. We went to the same school and we used to visit the woods afterwards. It was a great place for games.”

“They always are.” She looked sad for a moment and I wondered if she had ever ran through the woods with her husband. She changed the direction of the conversation. “When was he conscripted? He was conscripted, wasn’t he?”

“He was. It was later than you might have thought actually. He wasn’t old enough for the first year and then he injured his leg in a cricket match. It wasn’t until forty-two that he could fight. His parents tried to convince the army not to take him. He got angry because he thought they were just babying him. But, you see he was an only child and I think they were just scared...” I tailed off.

“And right to be so.” She gave me a pat on the hand. I was surprised at just how much I had already said. She was very easy to talk to. I thought I might as well tell her more.

“We were all scared, to be honest. The whole thing seemed slightly lacking in ceremony. He just took off one day with a bag of jellybeans and his lucky penny. (He found it in a puddle one day, when we were out for a walk.) He came back after his training and spent a couple of days with his parents and one day with me. We went to the woods and played around like children. It was all very stupid.”

“And what happened?”

I slowed my pace. “It was the strangest thing. He blurted out this proposal. He asked me to marry him, just like that. I agreed, of course. And then I waved him off to war and that was the last time I ever saw him.” I turned away to wipe a tear. It wasn’t a particularly sad tear. It was just that the memory was so lovely. I took a deep breath, composed myself and said briskly, “He was injured in combat and he died in the bunker.”

“What a terribly tragic story you have... but it is also very lovely, like a fairytale.”

She tilted her head to one side and looked so mysterious that I couldn’t help asking, “What about you?”

She looked around the bus and then leant towards me. I leant in too. She was the kind of person that made you feel as if you were being let in on a big secret. This was a pleasant feeling when I was between the ages; I wasn’t usually let into women’s confidences and I was too old for girlish whispering.

“Mine is quite different from yours. Are you sure you want to hear it?” she said, with an eyebrow raised. She was challenging me.

“Oh I do, I do,” I said.

Sitting upright again, she took her time with the introduction, but once she got going she was captivating.

“I am a war widow. My husband–of not very long, I’ve been widowed before–was conscripted. We lived just outside that town back there. He had bought a great big house for us. It wasn’t anything proper, though, because it was empty when we moved in. He was an orphan, you know, and he wanted to pretend we were from some established family. I tried to explain that it wasn’t that easy but he wouldn’t listen. It took us some time to be accepted into polite society and even then there weren’t many of those types about the area. Anyway, as I’ve said, it didn’t last long. He was conscripted.

“My husband was always gutless. He actually tried to invent some sort of medical condition.” She laughed through her nose. “The doctor saw straight through him. I don’t know what my husband was thinking; he was fit as a dog, anyone could see it. So he shuffled off to war. It was wonderful to have the house to myself for a while. Good things like that never last.

“In truth, I thought he would be killed for being such a coward.” I had never heard someone talk so and she must have seen the excitement in my face. “Yep, a total Lion, he was. That’s what killed him. One day, at the battlefield, he just climbed out of the bunker and ran. He didn’t run away, you understand. He ran towards them, the Nazis. People said, ‘Wow, he’s brave’ and ‘What a trooper’ and ‘He must be fearless’, but I knew the truth. He told me himself! He said, ‘I wanted to get shot, clean and simple’. He just wanted to die rather than suffer all that hardship of a real soldier. Well, the joke was on him.”

I was shocked by her tone, but I was also incredibly interested. “Did he die?”

“No. They threw a grenade at him. He was hit and badly injured, but not killed. He was also disfigured and it served him right. He was always vain as well as a coward. I thought he was very handsome at first. Then I learned exactly how much time he spent trimming his eyebrows and moisturizing his skin. He returned home as soon as he could—the hospital needed the bed—and from then on he was even more of a pain. He insisted being waited upon like an invalid, even though the only thing wrong with him now was his face. All the servants were stretched to their limit. He had such a temper with them, and with me.

“He ordered me about and said I should feel sorry for him because of everything he’d been through. I had to take down all the mirrors too; he hated to see himself so. Most of his time was spent in bed, moping and whining and pestering us all. I put up with it for a while, thinking he would get over it.” The serenity with which she spoke amazed me all the more.

“I suppose he didn’t get over it? Did he get ill again, is that how he died?”

“No, no,” she said. “He wasn’t really the slightest bit ill. That silly charade was kept up for as long as I could stand it. If you really want to know how he died, I’ll tell you.” She didn’t give me a chance to agree; she went straight on. “I realized, seeing him like that, what a dunce I had married. I was embarrassed really. He looked wasted away and obviously there was his face, spoiled by his own cowardice. I saw how pathetic he was. I’d always known but I had kidded myself that he would change. He didn’t.

“One night when it was unseasonably dark, I got up”—her eyes widened and I saw her eerily pale irises with tiny pupils—“and I went into his bedroom. He was sleeping soundly. Without anyone to see him, he was perfectly contented. I’d never seen him sleeping like that before. He has this silly little smile on his hideous face. You should understand that it wasn’t the disfiguring that I detested; it was the man himself and his ugly character.

“So, I went to his sink and found the straight razor that he used to use every morning to keep that square jaw smooth. Then, I leant over him”—she did the same to me now—“and I killed him.”

Her statement was so abrupt, so carefree, so confident, that it made me wonder whether I had misheard her. The twinkle in her eyes told me I had not. I was suddenly reminded of the closeness between us, two perfect strangers, one of which was a killer, and my breath got caught in my throat.

The woman sat upright in her seat again. Her eyes returned to slits surrounded with black makeup. She continued airily while I tried to comprehend it all. “And now, I am going to London. I shall set myself up a new life there. I’ll change my name, find a house, the usual, and then I will go searching.”

Curiosity got the better of me and I said breathlessly, “Searching for what?!”

A ray of sunlight shone through the window and lit up the woman’s face. She looked like the cat that got the cream. “I will be searching,” she said, “for my next husband.”

“But...” I struggled to fit all my questions into one. “But why?”

“Listen,” said the woman, looking peculiarly agreeable, “a woman widowed can collect her husbands’ wealth. Then, all she has to do to collect some more is get married again. She must move away as soon as possible so as not to be... looked too closely at.”

“So she just keeps marrying over and over?” I asked.

“Certainly not. At some point, when she has enough to support herself for the rest of her life, she finds a place to live alone. She becomes independent. She has no need for men or family, and she doesn’t have to depend on the charity of strangers. She can get a house all to herself, faraway from anyone else.”

I spoke as gently as I could, “Do you really think she’ll ever do this?”

The woman said with practised wisdom, “She will, just as soon as she can.” The bus slowed to a halt. It had already stopped a few times but I hadn’t taken much notice. I suddenly became aware of the busy city streets outside. When I turned back from the window, the woman had stood up. “This is my stop.” She strode off with her head held high. She paused at the top of the bus steps, looked back and winked at me.

I stared after her as she walked up the street. She was by far the most eccentric creature I had ever met. Her story was extraordinary. It had such detail and such emotion to it. I wondered what kind of woman she was. None that I had ever known, that was for sure.

“What did she say to you?” asked an eager voice.

I regained awareness of my surroundings and noticed an old woman on the seat across the aisle, looking at me with an open mouth. I had noticed the little granny get on the bus and sit towards the back a short while before. I didn’t have the faintest idea what she could mean.

“I’m sorry?” I said.

“What were you talking about?”

I couldn’t figure out why she was so fervent about it, so I gave a small answer. “Nothing of great significance.”

“What do you mean? Aren’t you amazed? Can you believe it? This will be a story to tell your grandchildren.” Her thin little lips were stretched from ear to ear.

“Whatever do you mean?” I said quite plainly.

The granny looked shocked. “You mean you don’t you? Oh my dear, you’ve just met Ivy Johnson. She wrote The Black Widow. Haven’t you read it?”

Of course I’d read it; everyone had. But if she was the writer that would mean...

I shot upwards, struggled to open my window and leant right out. The bus had already started up and we had just gone past her so I could do nothing but stare. The woman waved an elegant hand at me. With the breeze whipping my curls about my face, I watched her until her eyes were black dots, her lips a red pinprick and her dark hair the width of a fingernail.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.