All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

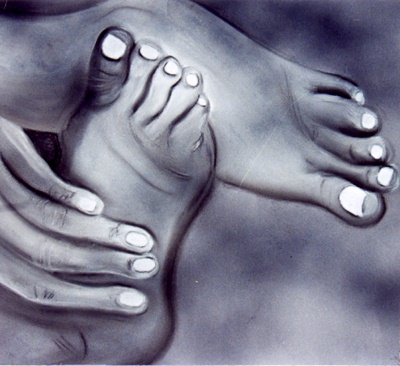

The Footwasher

A week has passed since that day. Nothing has changed.

But everything has changed.

I had heard stories, impossible tales of the lame walking, the blind seeing, lepers cleansed, demons chased out, even a dead man coming alive again after four days in a tomb, but quite honestly, I had not believed them. Those I came in contact with spoke of a teacher, a Rabbi, a man straight from God who traveled and taught, leaving miracles in his wake.

Then they said he was a Nazarene, and I stopped listening. I had lived in Israel long enough to know that nothing good came from Nazareth.

I am not a Hebrew. In truth, I am not entirely sure of my ancestry; my father sold me away from home when I was very young to pay a debt. For all I know, I could have been born a Roman citizen. But the Jews look at me and scorn me, calling me “Gentile.” I am not the youngest or newest slave in my master’s household, but I am the only Gentile, and therefore the lowest of them, relegated to the nastiest jobs: feeding pigs, handling waste, washing feet. Even my fellow slaves disdain me.

At my master’s command, I observed what Hebrew customs he required me to, but I did so without enthusiasm. No God had ever cared for me; no person had ever cared for me. I had seen no kindness in my life. I did not believe in a God.

The Nazarene stayed in my master’s home for the Passover festival. The others flocked him, but I just went about my work after washing his feet and those of the men with him. The work needed doing, and I had been beaten for failure to do it before.

As the night fell and the others finished their chores, they all received food and retired to bed. Realizing I was the only slave still awake, I slipped up to the upper room when I finished my chores; someone had to be responsible and check on and wait on the guests. I opened the door slowly, just a crack, not caring to interrupt an obviously private meal.

The thirteen Galilean men lay on the couches some of the others had put together earlier that day, eating the traditional Passover meal; I had served it enough times to know what it contained: lamb, bread without yeast, bitter herbs, and so on. But as I watched a moment, one—the teacher, who the other men called “Lord” and “Rabbi”—stood and took off his outer robe. He wrapped a towel someone had been careless enough to leave around his waist, pouring some water into a basin, the bowl I usually used to wash feet.

Then he knelt beside the nearest man and began to wash his feet.

I gaped. A man called “Rabbi,” “Lord,” even “Messiah” by a few of my fellow slaves, knelt to wash feet. What man would put himself in that place of his own free will? Why would a man said to be a prophet voluntarily do a job relegated to slaves—and not just any slaves, but the lowest in a household! What man would lower himself to the point of having no stature whatsoever? To the point of avoiding eye contact with freemen? To the point of washing feet filthy after a long journey?

To my level.

His companions, once he began, fell silent, watching in almost as much openmouthed shock as me. They said nothing, afraid to interrupt, but clearly disapproving of what he was doing. Slaves’ work. My work. Slowly, he went around to all of them.

One protested, asking in shocked disbelief, “Lord, are you going to wash my feet?”

The rabbi replied, “What I am doing you do not understand now, but afterward you will know.” What? What was he doing?

“You will never wash my feet,” his friend protested firmly. “Ever!”

“If I do not wash you,” the teacher replied firmly, tone like a disciplining parent, “you have no part with me.”

That made even less sense. The look on the man’s face mirrored my confusion, but added a bit of panic to it. “Then…Lord, not only my feet, but also my hands and my head.”

“One who has bathed,” his lord told him, “does not need to wash anything except his feet, but he is completely clean. You are clean, but not all of you.” His eyes passed over the whole room as he spoke, and I got the impression the statement was profound, a kind he made often. After letting the silence sit, he continued foot washing until he had done it for all of the men in the room.

When he stood and sat back where he had been eating, he spoke again, addressing the lingering looks of confusion pointed his way. “Do you know what I have done for you?” he asked, apparently not expecting an answer. “You call me Rabbi and Lord. This is well said, for I am. So if I, your Lord and Teacher, have washed your feet, you also ought to wash one another’s feet. For I have given you an example that you also should do just as I have done for you.” He paused for a moment, to let that sink in. I still did not understand: how was washing feet an example? How was that, the lowest manifestation of slavery, a lesson to them?

Then his eyes fell on me, standing all but hidden in the doorframe; I held my breath, waiting for him to expose me and ask what I was doing there, how long I had been listening, but he did not. He smiled knowingly, with a gaze that pierced straight through me. I felt like he could have told me my life story, such as it was, just looking me in the eyes. This Hebrew rabbi looked on me, a Gentile slave, a footwasher, dressed in rags and filthy, beaten down by life, with more compassion, kindness—love, even—than anyone ever had.

I could not tell if he was truly what people said he was, but I knew one thing: this man was far different from any other.

Slowly, conversation started back up, the men eventually discussing their own greatness; I knew I should probably go in, ask if they needed anything, but the teacher said nothing about my listening, and something about him…I could see why people wanted to listen to him.

His companions argued among themselves, vying for a place as greatest among them. Their teacher met my eyes again as they did and shook his head with a smile, as if they were children. He spoke again, slightly scolding, saying, “Whoever is greatest among you must become like the youngest, and whoever leads, like the one serving. For who is greater, the one at the table or the one serving? Isn’t it the one at the table? But I am among you as the one who serves.”

I could not help thinking his words were directed at me. Of course I gaped, amazed at his implication: that service was an honor. He inclined his head in my direction slightly, acknowledging my presence, leaving me even more breathless than before.

A tight, rough grip on my shoulder jerked me out of my thoughts. “What are you waiting for?” my master demanded gruffly, loudly enough to get the attention of the guests. I flinched a bit. “Get in there,” he ordered.

“Yes, Master,” I muttered, head down, pushing open the door all the way. They did not need anything, and I was dismissed for the night after that. Usually I fell asleep immediately in absolute exhaustion, but that night I lay on my mat for hours, thinking. Trying to figure out why a rabbi would belittle status and elevate lack of it, especially if a quarter of the rumors of his miracles were true.

I could not get the image out of my mind: a respected teacher, called “Lord,” with a towel wrapped around his waist, washing his students’ feet. Washing their feet. Willingly, silently, as if he were in my position. I did not understand it. My questions kept going in circles.

The next morning, Jerusalem buzzed with the news that Jesus, the Nazarene rabbi, had been arrested and was being tried for heresy before the Sanhedrin. I could not believe this; hadn’t he just eaten in my master’s home? For once, I was grateful that the other slaves in the household gossiped endlessly, as I picked up what was going on from their chatter.

The Sanhedrin, unsatisfied with the extent of the trial, appealed to the Roman regional governor to have him executed: crucified. I had seen crucifixions before—albeit very very few—and I could not imagine a worse way of dying. He was convicted; I did not see his execution, but they said the earthquake that afternoon, the one that shook the whole city and tore the Temple curtain in half, coincided with the moment of his death.

That convinced me that a good man, possibly even a man of God, had been unjustly killed.

The Sabbath passed uneventfully—I did work that according to my master was “not technically work” while the others did nothing but go to the Temple—but the following morning, when my chores took me out of the house for a bit, the strangest thing happened. An impossible thing, akin to the lame walking, the blind seeing, and lepers cleansed.

I carried a load of waste to a place outside the city walls, and as I left the crowds of Jerusalem for the isolation of the surrounding land, I saw another person. This in itself was unusual, but not unheard of; if ever I saw anyone else here, he was doubtlessly, like me, the lowest slave of his master’s household. Once or twice he was even another Gentile. Always, he would catch sight of me; we would exchange a glance, sometimes a word, and after would never see one another again.

This time, however, the man I saw stood up straight, head erect, wore sandals, fearlessly looked me in the eyes. With a knowing smile, he inclined his head in acknowledgement, a respectful gesture only one person had ever given me before.

But that man had been executed three days ago.

But he stood there alive, looking at me expectantly. “Rabbi…?” I asked in disbelief, gaping, not knowing what else to call him, not caring that I was not supposed to be speaking to him. “Are…you a ghost?” I had not believed in ghosts, but how else could a dead man be standing in front of me?

And of all the people in Jerusalem—of all the people in Israel—why would his ghost appear to me?

“I am not, Kallias,” he replied with the same knowing smile, not fazed that a Gentile slave had spoken to him out of turn. I had not told him my name. “Touch me and see; a ghost does not have flesh and bones, as you see I have.”

He held out his hand, and hesitantly, I touched it, amazed to hit flesh. I saw a wound in his wrist: a hole from a nail. This man, this good rabbi who was willing to wash feet, had been executed by the Romans, and yet stood alive and talking to a slave—a foot washer.

Perhaps there was a God after all.

A rumor came to mind, an impossible one the others had been whispering for days. Softly I asked. “Rabbi, are you…you’re the Messiah, aren’t you?” The one who would save the Jews. But if he was, then why was he here, taking the time to speak with a Gentile?

“It is as you have said,” he replied. “But I came not only for the Jews, but for you as well.”

I went back to my master’s house in a daze. When asked why I was acting strangely, I replied breathlessly, “Jesus of Nazareth? He is the Messiah, and I have seen him alive.”

I came not only for the Jews, but for you as well.

A week has passed since that day. Nothing has changed.

But everything has changed.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 18 comments.

I wrote this in light of Easter, after a night service discussing the Last Supper. Hope you find this point of view different!

Credits: Most of the dialogue is taken from John 13:4-15, Luke 22:26-27, and Luke 24:39. The name Kallias is Greek in origin—hence Gentile—and not based on anyone in the Bible.