All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

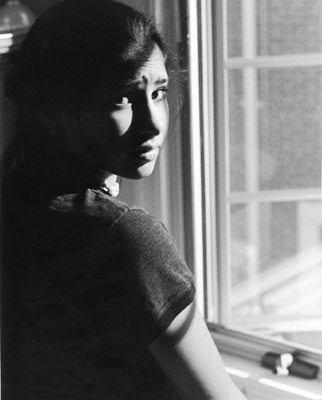

Hydrangea Eyes

She lived life through her flowers.

The first time, I saw her was in the hallway, and she was carrying a tiger lily in one hand. There was a popular girl making fun of her, but she just kept walking.

The second time was the first day of school. She was in two of my classes. She was wearing a wreath of dandelions in her hair. I didn’t give her much of a second thought.

The day we were assigned as lab partners, she had a stem of baby’s breath stuck behind her ear. I learned her name was Jennifer, and that was about it. The first week we worked together she went through tatania, tulips, foxglove, and jasmine. The last day, she wore lavender.

“Is lavender a flower, or a weed?” Some girl laughed from behind us. Jennifer turned.

“It depends on who is wearing it,” She said. “On some people, it’s a flower. And on others,” She smiled, placing a swig of lavender onto the girl’s desk, “It’s a weed.”

One Fall day we walked home together and I found myself noticing how the hydrangea matched her eyes.

At the first football game, I scored a touchdown, and when I turned to the band she was at the railing cheering, forget-me-nots knotted into her light brown braids, her flute being pumped into the air.

On the next day, she was wearing a red poppy behind her ear, and we walked home together.

The next day, she was wearing a daffodil yellow scarf, and we both held her sunflower in both hands as I kissed her. When I pulled away, both their faces were pointed into the sun. And both were glowing.

She was wearing lily of the valley on our first date, when I first called her Jenny. We went to the mall and just wandered, listened to music in the electronics store, fenced around the drugstore with wrapping paper rolls, and ate ice cream in the food court.

Jenny left her hair half up for her birthday, and tiny pink teacup roses were knotted all in her hair. I saw her for the first time at our lab table, and I handed her three snapdragons. She smiled up at me as class began.

On Columbus Day, she wore sweet pea and lilacs tied into one long braid.

“Not for Columbus,” She explained, with a wrinkled nose, “For the Native Americans.”

“Of course,” I laughed, and hugged her.

The first time I told her I loved her, she had a cherry blossom in her hair. It was after a long walk home, in the bitter October wind, when she nestled into my arms, and the three words surprised us both. She smiled knowingly, whispered a reply, and kissed me, her arms around my neck, before she left. I sang Beatles songs for the rest of the day.

For Halloween, I was a vampire. She was a fairy, and she was covered in yellow carnations and daisies, knotted into her hair, sewn into her dress, her wings, and even her shoes. She had a crown of white morning glories.

It was buttercups she held the first whole night we spend together, falling asleep under a warm blanket while stargazing, her head tucked underneath my shoulder. We both woke up soaked, covered with dew.

At homecoming, she presented me with a bouquet of poppies after I became Homecoming King, and we danced together in the warmth of the school gym.

She came over to my house for Thanksgiving, and met my family. My mother was delighted. She was wearing a wreath of orange and yellow chrysanthemums (or, as normal people call, them, just mums).

The first day of winter she had peonies.

“The essence of winter,” She said quietly, a small smile on her face, “They’re like snow drops. They hold onto the cold for us until next year.” (She had snowdrops on the next day).

On Christmas Eve, she gave me a candy cane and a kiss, and I gave her her chocolate. She had red carnations in her hair.

All was happy.

Then it started to snow.

She had never been in real snow before, and that night she ran out to get flowers for the occasion. When she came back with wilted violets, she looked a bit in shock.

“What’s wrong? Jenny?”

“Nothing. This…was all they had,” She said, and then she smiled, and stuck the violets into her buns. “Let’s go make a snowman!”

But it kept snowing, and soon I told her that she had to go home, and stay there until it had stopped. I gave her a single orchid from a vase of my mom’s as she left. Her face brightened straight away.

“Good-bye,” She whispered with a hug.

“Be safe,” I answered, and she left, soon disappearing into the snow.

It was one of those serious, nine-footer type blizzards, and everyone was totally shut in. The town shut down, school was canceled, and the stores were closed. The heater broke, and I was so preoccupied with beating off the pneumonia to realize the phone lines were up, until the blizzard was over.

“Hey, Jenny. What flower is today?”

“Oh. None. Can’t get away, with the blizzard.”

For some reason I had never thought of where Jenny actually got her flowers from. I had always kind of wondered if she just had a greenhouse in her basement or something.

“Are you okay? You’re talking kind of high-pitched. You sound off.”

“Oh, it’s…Well…have you ever seen a cartoon, and they’re trying to like keep the dam from leaking, so they stick a rock in it or something? And the rock’s the only thing keeping that dam from bursting. And you start thinking, how in real life, every time a rock gets worn down, you’d have to replace it with another rock. But then, eventually you run out of rocks. You know?”

“No...not really. But, uh, hey, I think I should be able to get over to your house sometime soon, all right?”

“Sure. Yeah. Okay. See you.”

I couldn’t go visit, though, it turned out, because my mom actually did get pneumonia, and my dad had to work. So I took care of her until, one day, when she was starting to get better, a doorbell rang.

It was two policemen.

Jenny was missing.

I joined in on the search right away. Searched the house for clues with her dad, who had Jenny’s hydrangea eyes; and the town for her with her mother, who had her high, pale cheekbones. We didn’t find anything, until I did.

Three days later was when I found the brown stem in a puddle of melted snow under her window, with what looked like a wilted orchid. It was pointing towards the forest.

Brown stem.

Hydrangea eyes.

“Jenny! Jenny!”

Deeper and deeper into the woods, sunlight shining through the leaves.

“Jenny!”

And then I saw the violets.

Violets, for frozen.

Violets, for ice.

The violets.

The hydrangea eyes.

The daffodil scarf.

The violets.

The frozen.

The yelling. My yelling.

The hand that pulled me away.

Later, flowers.

So many flowers.

Mums. Roses.

Hydrangea.

Her hydrangea eyes.

And a brown stem for the woods.

Violets for frozen.

Violets for ice.

Daffodils for her scarf.

Hydrangea eyes.

Hydrangea, her eyes.

And roses.

Roses.

Black- to match the ashes.