All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

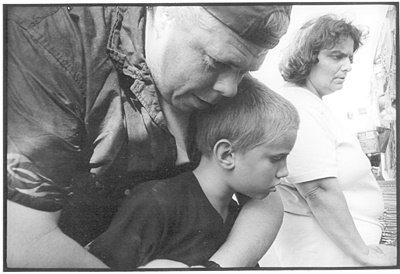

My Boy

“Poppy, Poppy, Poppy!” seven-year-old Kigun O’Conner sang happily, dancing in circles around his grandfather. “When will we have breeeeaaaaak-faaaast?”

“Soon as Gramma gets back,” Grandpa O’Conner wheezed lifelessly as his spectacled eyes skimmed the newspaper halfheartedly and his wizened old hand moved of its own accord to flip the page, dark veins popping out over his snow-white skin like a horde of diseased purple-blue worms. Kigun rounded in front of him again, knobby knees buckling dangerously and muscled calves rippling from the exertion, and Grandpa O’Conner reacted by shoving his generic, wide-brimmed, beige fishing cap down farther over the balding crown of his head.

Kigun halted in his dance and wobbled clumsily for a minute before righting himself, peering out of the corner of his vibrant seaweed-green eyes all the while to see whether Grandpa O’Conner would look over and watch to be sure he was okay. Grandpa O’Conner sighed and didn’t look up.

“But, Poppy….” Kigun waited for recognition, shuffling his brand-spanking-new, navy blue tennis shoes in the loose earth that had assembled in the no-man’s land between the calf-length grass that spanned the whole two acres of front lawn, and the crumbling cement sidewalk that led up to the front door of Grandpa and Grandma O’Conner’s decent-sized home.

“Go on-a frolic some-ere else,” Grandpa O’Conner murmured, garbling the words between the time they shot from the neurons of his brain to the moment that his lips parted a bare half centimeter to let the sound escape.

“But I’m huuuuungry, Poppy,” Kigun whined, his young voice reaching a falsetto that served to wound Grandpa O’Conner’s delicate ears- permanently, he thought, as he tried to refocus on the small town murder that he’d been reading about. “It’s already 10:14 an-a twenty one- two- no three seconds!” Kigun informed him proudly, displaying the thick black band of his new watch right in front of his grandfather’s eyes. “Do you see that, Poppy? See that hand moving like that? Isn’t that so cool?”

Grandpa O’Conner turned another page and smoothed out the crease with one swift swipe of his wrinkled hand. “That’s so cool, Kigun.”

“You didn’t even look!” Kigun said indignantly.

“No?” Grandpa O’Conner murmured in a preoccupied manner. He reached up to take off his glasses and pinch the bridge of his nose where two little red indents had formed. Then he put the glasses back on and trailed his finger down the newspaper until he found an article that looked halfway decent- none of this stuff is gossipy enough, he figured with a sad shake of his head. Quickly, he righted his fishing cap until it was perched just so again. That’s just it, he thought. There’s just not any good gossip anymore. It’s all about nut heads that no one knows. Where are the troublemaking celebrities, for Christ’s sake? This isn’t the bible or… he couldn’t think of anything else to think so he shook his head again, and righted his cap and started reading the article so that he wouldn’t have to think.

“Poppy!”

Kigun had shrieked his shrill little voice straight into Grandpa O’Conner’s eardrums. Grandpa O’Conner jumped a good foot in the air, and his buttocks hurt rather badly when he thumped back down into his lawn share. Finally, he looked up from the paper.

“Kigun!” he retorted. “How dare you be so rude!”

Kigun glared right back at him, arms wrapped snugly across his torso, feet planted shoulder width apart, toes pointed glaringly straight in front of him. He was wearing his favorite jeans, Grandpa O’Conner registered immediately. The ones from his father. Mr. O’Conner wasn’t good at wrapping presents so when he’d sent the jeans, they’d been just rolled up in a dozen paper towels. It had been just the sort of luck that the O’Conners were used to that it had been pouring rain the day of the delivery so the papers had been all soaked through. But it still didn’t even explain how the gaping hole had gotten right on the left thigh so that Kigun’s boxers, when he wore them, were visible, or else his skin was on the days that the boxers didn’t adorn him. Grandma O’Conner was always saying to Grandpa O’Conner how very inappropriate it was for Kigun to be dressed in such “explicit articles of clothing, Joe, really, they’ll think he’s in a gang, how can we let him go to town dressed like a sl**?”

“Sl**s are women, Helen,” Grandpa O’Conner always said to that. “And no one will think that shrimp’s in a gang. He couldn’t even handle a pocketknife, I’d bet you.”

“Well,” Grandma O’Conner would sniff, flustered. “Well!”

“Well what?” Grandpa O’Conner would ask, just to see her hands flutter down to her hips.

“Well- my word!” she’d announce importantly. “Lord, my dear word.” And that would be that as Grandpa O’Conner would deign not to broach the subject again.

Now, along with the tattered jeans, Kigun had on a collared t-shirt the color of which matched his vibrant eyes exactly, causing them to pop out marvelously and draw the onlooker’s attention. Kigun O’Conner’s hair was a creamy, butter-blond, highlighted syrupy golden-brown at the surface from the sun’s rays. It was long and tousled, sticking out over his ears, with the fringes of his bangs clouding his eyes, and the longest curls residing lightly at the nape of his neck where they bobbed in time to the rhythm of his steps.

Kigun snapped Grandpa O’Conner back to the conversation with a start: “You’re being ruder, you know, Poppy.”

“Am I?” He’d quite forgotten what they’d been discussing over the course of his inspection.

“See! You just did it again. You aren’t listening to me, Poppy!”

“You’re right- I’m sorry. What were you saying?”

“You didn’t look at my watch,” Kigun announced, holding it out again.

“It’s a nice watch, Kigun.”

“I know,” said the boy proudly. Grandpa O’Conner nodded agreeably and then returned to his paper. Nothing. There was nothing gossipy. “Sex scandals?” he muttered inaudibly to himself under his breath. “Drug dealings?” No. Nothing. “What’s gotten into these celebrities? Why is everyone so fine and dandy all of a sudden? Bring on the hippies.”

“What are hippies, Poppy?”

Grandpa O’Conner readjusted his fishing cap and squinted at his grandson. Kigun had begun to circle him again. “Never you mind.” Kigun danced harder, swinging his hips. “The door’s unlocked, boy. Do you need the facilities?”

“No, sir,” Kigun crowed.

“What’s the dance for then? Rain dance? We don’t need no more rain. There’s been too much lately.” Grandpa O’Conner shut the paper with a flourish, smacking the two sides together crisply. Then he leaned back in his lawn chair and breathed in the aroma of a sweating summer of ripe fruits as he watched a multitude of ants swarm up the sidewalk on their way to infiltrate the air-conditioned house.

Kigun paused in his rigorous movement. “Popeeeeeee,” he said, drawing out the word for emphasis. “I like rain.”

“Well, I don’t. Nothing gets done during the rain.”

Kigun plopped down on the grass and stuck his legs out in front of him. Then he looked around expansively before settling his gaze pointedly on his reclining relation. “Nothing’s getting done now either, and it’s sunny. And real hot,” he added as an afterthought, feeling an unbidden bead of sweat trickle down his spine.

“Well, till Gramma gets back with the breakfast stuff, there ain’t anything to do but read the paper.”

“Is there anything good?” Kigun asked curiously, trying to crane his neck from the ground to no avail, and then, as Grandpa O’Conner shook his head, Kigun changed tacks. “I’m real hungry.” He looked suspiciously at his grandfather out of slit eyes. “You’re absolutely, positively sure there’s no food in the kitchen?”

“I never said that…. There’s chicken… and turnip stuff…. And squash, I’ll bet.”

“But that’s not breakfast stuff,” Kigun said, slumping down farther in the grass. “I’m so hungry- for breakfast.”

“I didn’t say there was breakfast stuff. Just said there was stuff. You didn’t ask for breakfast stuff.”

“Sure I did.”

“No you didn’t.”

“Well I thought it.”

“That doesn’t count, Kigun.”

Kigun jutted out his lower lip. “Yeah it does.”

“No it doesn’t,” Grandpa O’Conner said, raising his eyebrows again. “I don’t read minds, boy.”

“If you tried you could,” Kigun muttered. “Instead of just sitting around all day in your chair.”

“No I couldn’t.”

Kigun stood up and shook his head back to get rid of the irksome bangs. “You need a haircut,” Grandpa O’Conner said, scrutinizing him.

“No I don’t. I need a hairscut.”

Grandpa O’Conner sighed and smelled the fresh air again. Looks like it’ll rain soon, he thought glumly. Dog gone rain. You really ought to leave us be. “I don’t do hairscuts. Just a good dandy haircut like my grampa and my papa always gave me. Well,” he amended as a thought came to him. “They never gave me a haircut a’ tall. It was my mama usually. She’d set all of us down in the kitchen and pick up her scissors…” Now Kigun sighed too. He steepled his fingers together and mouthed the words here is the church; here is the steeple… “Go on an play,” Grandpa O’Conner said, cutting himself off. “You weren’t even listenin’ to me. Go on then. Get.” He slowly brandished a hand, swatting limply at the boy who veered off to the side, out of his grandfather’s reach.

Kigun began pacing again, staying in Grandpa O’Conner’s line of sight. “I don’t want to. There’s nothing to do.”

“In my day I found stuff to do.”

“But you’re supposed to entertain me. All my friends’ grandpas an grammas entertain them.”

Grandpa O’Conner shuffled the newspaper around on his lap. Jesus Christ, these newspapers now days. There was nothing interesting anymore. No one cared about the garage sale in Jerusalem. “Well if everyone else’s grammas and grampas went an jumped off a bridge, you bet I’d stay right here and read my paper ’stead. And Gramma wouldn’t go neither.”

“I’m really hungry, Poppy.”

Grandpa O’Conner slapped the paper down onto the grass next to the chair and reached into his back pocket for a flattened cigarette. “You know what, Kigun O’Conner? You is never- never, never, never around during chores time or when we’re watching a movie or when we have to go to a picnic or some mat, but when breakfast is coming around or I’m busy with the paper or your Gramma’s a cookin’ in the kitchen, then you get right under foot and want a demand some of our time!” He shuffled through his other jeans pocket to retrieve his lighter and quickly flicked the switch so that a spout of fire shot up. “Now I’m busy, boy, and you ought a go find some entertainment on yer own, you hear me?”

“Poppy…” Kigun wheedled, shoving his bangs off his face with the flat of his hand. He produced his best puppy dog eyes and stuck out his lip. “Can’t we play a game until Gramma comes back?”

“No. I’m reading.” Grandpa O’Conner looked wistfully off down the road. When is that old lady going to see fit to come back and shut this kid up, he wondered. Where’s she at that she couldn’t bring Kigun ‘long? Better yet: where’s that old son of mine? Why ain’t Calvin bringing his kid to all his stuff ‘stead of droppin’ him off here?

Kigun abandoned his pleading eyes, instead raising his eyebrows. “That looks like smoking from where I’m at.”

“You cheeky boy,” Grandpa O’Conner warned. “Don’t mess with your poppy.”

Kigun contemplated saying something, opened his mouth, decided against it, shut his mouth, and then decided to just go for it. “Smoking is bad, Poppy. That’s what Missus Hanson says.”

“Is Missus Hanson God?” A ring of smoke curled from Grandpa O’Conner’s mouth.

“Naw- bu-”

“Is she Jesus?”

“No, she ain’t, Poppy, but-”

“She the holy ghost then?”

“No, Poppy!” Kigun shouted, waves of frustration vaporizing around his skin. “Mrs. Hanson isn’t God or Jesus or the holy ghost or nothing like that.”

“Then how’s she know smoking is bad?” Grandpa O’Conner took a nice long drag to infuriate his grandson.

Kigun swiped the hair from his eyes. “I don’t know! It just is. All my friends say it too. She knows stuff, Poppy,” he warned solemnly.

“I know stuff too,” Grandpa O’Conner said in a final sort of tone. He dropped the cigarette and smashed it into the ground with one of his big, brown boots that he’d left his father’s farm wearing and never let go of. Kigun groaned in exasperation and Grandpa O’Conner arched his eyebrows at the boy. Then, looking behind him, he said contentedly, “Lo, there, Kigun, Gramma’s back home.”

Grandma O’Conner trudged up the vacant street humming tunelessly to a church hymn and swinging a parcel of bacon in a plastic bag on one hand. She reached the O’Conner mailbox, and stayed her feet long enough to grope in the black interior and withdraw a flimsy white rectangle. Then she started up walking again, her stride short so as not to tear the rather snug paisley dress she was wearing.

“Hallo, Kigun!” she cried in a warbling, wobbly sort of voice that still managed to soar lightly on the wind and touch down on the child’s ears like the breath of a butterfly. “Joe,” she added primly to her husband. Grandpa O’Conner, watching her, touched his hand to the brim of his fishing cap and lifted it off his head an inch or so as he inclined his chin out to the side like an elderly dancer who had been sedentary for too long.

“Helen,” he returned, placing the paper back on his lap and turning to a page at random. Jesus Christ, the garage sale in Jerusalem again. Is this world news, he wondered. So then he had to turn back to the front to see the region that the paper encompassed. “The city paper,” he muttered. “Isn’t there any garbage in the city? Where is the dang gossip?”

“Gramma!” Kigun shrieked, tearing down the lawn toward the plump figure. He threw himself at her and she caught him, laughing, and held him to her pillow-like stomach, clasping her arms behind his slender back like a crisscrossing seat belt. “You’re too old, Joe O’Conner,” she said laughing. “Lo, Kigun,” she said after a minute had passed and she had let go. “Come now, get off. Yes, get off. You’d think you’d not seen me a year with this reception, child. My stomach’s too large for that pressure. It needs to breathe. Go on, boy.”

“But I missed you, Gramma,” Kigun moaned, resignedly loosening his grip. Grandma O’Conner snagged one of his small hands in hers, felt something sharp, and lifted the hand to examine it, tut-tuting as she did so. “Child, child, child. You need a nail clipping.”

“You just did it.”

“A week ago,” she corrected.

“Only a weeeeeeek,” he moaned.

“Oh, hush,” she laughed. “It doesn’t hurt any. You’re a growing boy. You need regular nail clippings. Why Joe couldn’t do it…”

“He can’t get his fat bum outta his chair,” Kigun informed her, swinging their hands back and forth.

“Oh,” Grandma O’Conner said, laughing. She glanced over at Grandpa O’Conner. He had returned to his paper.

Kigun pulled his hand away, clutching the tips of his fingers protectively. “I think they get hurt when you clip them.”

“No-” she began.

“Well then they get sad, at least. They get scared ‘cause they’re all alone without their mommy.”

“Who’s their mommy?” Grandma O’Conner readjusted the package of bacon on her other arm, and noticed simultaneously that Kigun was wearing his “sl** pants.” “Why are you wearing those-”

Kigun interrupted quickly- with a glance over at his grandfather- “Poppy said I could. I wasn’t going to. But he said I could. He came in my room and said it.”

“He never goes in your room, Kigun.”

“Well he did today,” Kigun said defensively, wrapping his arms back around his torso. “He said I could wear them.” He looked around for a distraction. “What’s that?”

“Letter,” Grandma O’Conner said.

“Who from?”

“Hold this.” Kigun nearly fell over under the weight of the bacon but he was too excited to notice. Jostling it around until he settled with gripping the package tight against his chest, he watched his grandma flip the envelope over.

“It’s your papa,” she said, the surprise coating every syllable. “It’s Calvin,” she called out to Grandpa O’Conner.

“That Calvin?”

“Yes. Your boy.”

“I don’t have a boy named Calvin. What kind of idiot name is-”

“Watch your language.” Grandpa O’Conner gestured her chin in Kigun’s general direction. “There’s young ears here.”

Grandpa O’Conner waved away her concern. “Oh, that kid has a bigger vocabulary than me, Gramma. You tell him to watch out for old ears.”

Kigun and Grandma O’Conner reached Grandpa O’Conner’s lawn chair and Grandma brandished the letter in front of his nose. “Calvin O’Conner, sir. Your son, you lazy bum of a man. Don’t you say you forgot your son.”

“I forgot my son,” Grandpa O’Conner drawled lazily. “Yup. I forgot him. After all the good things he done did for me, I forgot him.”

“He’s your son, Joe. Don’t you forget that,” she warned in a tone that left no room for jesting.

“He’s an idiot. What’s the masculine word for sl**, Helen?”

“I don’t know,” she said firmly.

“Well, then, he’s a male sl**.”

“What’s a sl**?” Kigun chirped.

“Reason you’re alive,” Grandpa O’Conner said immediately, before Grandma O’Conner could interject.

Kigun changed subjects before anyone else could. “Poppy,” he said inquiringly. “Why do you hate Daddy?”

Grandpa O’Conner stood up and yawned exaggeratedly, raising his arms to the sky so that his belly fat wobbled inside the tight cocoon of his button-down shirt. “What daddy?” he said, and then he began to trudge up to the house. “Come on, woman. I’m hungry.”

Grandma O’Conner tore open the letter while Kigun plopped down in his grandfather’s lawn chair. “He’s visiting, Joe!” she called to her husband’s retreating back.

“When?” he barked gruffly.

There was a slight pause. Kigun listened to a pair of birds shrieking at each other from a tree a few yards away. Probably fighting, he reflected impassively. Vaguely, he wondered what about. “Today,” Grandma O’Conner murmured, jaw dropping. “You’re gonna need a wash,” she added, catching sight of Kigun’s ears.

Kigun bounded up. “Lemme see, Gramma,” he begged hysterically. “Daddy’s coming today! Where is he? Where is he, Gramma? Is he coming right now? Is he? How long is he staying, Gramma? Is he staying a long time? Is he bringing presents for me. It was my birthday two months ago, you know, and he only sent some money.” He wrinkled his nose. “Not even a lot, you know. Just a little bit. Wait- is he taking me back with him when he goes? Is he?” He stopped talking long enough to let his heart settle. “Well, Gramma?”

“No,” she said. Then she began walking away toward the house, staring down at the letter.

Kigun felt a sudden, heavy sense of letdown, the same way he always felt after he ate a lot of food and got full and then found out that there was a huge pie on the way out of the oven. But this was worse, because he felt something begin to burn his throat, and sting his eyes. He swiped carelessly at his eyes, feeling the sting, wondering how bees had suddenly figured out how to be invisible.

Then he turned tail and ran after his grandma. “Hey! No what, Gramma?”

“He isn’t staying,” she said abruptly. “Just coming to see you an hour ’fore he has to go.”

“Go where?” Kigun demanded.

“Calvin was fired,” she said absently. “Cause his birthday is today and he wanted to see you and they’d only let him go if he got fired. So he got fired. So he could come see you an hour.” The letter fell limply to her side. “You got a good daddy, Kigun,” she said firmly.

“So where’s he have to go?”

“Just away,” she said.

“Is he bringing any presents?”

“No presents,” Grandma O’Conner said. “Just him.” She paused. “But you know, son, that’s a present right there.”

Grandpa O’Conner turned around at the door to let his wife catch up. “Damn boy never did anything right. His whole damn life is a mistake.” Grandma O’Conner brushed her eyes covertly with the back of her hand. “I don’t want him here,” Grandpa O’Conner yelled, thumping his hand into a windowpane so hard it cracked. He gazed down at the little trickle of blood on his hand. “He’s a damn idiot. And you’re a fool for having him, woman. Damn ovaries. Ought of a been shut up.”

“Just say you love him, Joe,” Grandma O’Conner pleaded. “Just once say you love Calvin. Please. Just once.”

When Grandpa O’Conner turned to look her full in the face, his eyes were ugly and black, his skin like ash. He spoke coldly, precisely, locking his eyes onto hers. “I don’t love your kid, ma’am. I hate that kid- and he hates me. Now go cook that bacon.” He turned to Kigun who stood timidly in the doorway, defined by the sunlight swarming around him even as he tried to blend in to the outside world. “C’mere, Kigun.” Grandpa O’Conner sat down heavily at the table, letting his hard features soften like butter in the sun. “Let’s play a game. Chess… or dominoes. We should play dominoes. That’s a good game. Your favorite, boy.”

Kigun began to walk. He walked firmly in a straight line, past his grandpa, past his grandma, keeping his eyes averted straight ahead. “I don’t want to play a game, Poppy,” he said, the bitterness scarcely concealed behind a façade of calm. “I think I’ll just go to bed until Daddy gets here. My daddy loves me.”

_____________________________________________________________________________________

Break #1

“Why didn’t Daddy come?” said Kigun curiously, darting around Grandpa O‘Conner’s lawn chair the next morning, same as always.

“He was busy,” Grandpa O’Conner said, staring down at the same article he’d been watching for the last twenty minutes. He was frozen, rigid in his chair. He didn’t believe what he was reading. Kigun didn’t notice any difference in his behavior.

“But he said he’d come,” he pouted, plopping onto the ground in order to pick a handful or two of grass. “Doesn’t he still love me?” the boy asked quietly, trying to appear unconcerned.

“He was too busy.” Grandpa O’Conner folded the paper with shaking hands and tossed it on the ground, forcing himself to gaze around for a distraction, any distraction at all.

“Are you sure he still loves me though?”

“Yup,” Grandpa O’Conner said shortly.

“Oh,” Kigun said, and Grandpa O’Conner knew he wouldn’t bring it up again.

“Oh, look at that, how bout it?” Grandpa O’Conner said suddenly, in a falsely cheery voice that didn’t suit him.

“Look at what?” Kigun wondered aloud.

“Why…” Grandpa O’Conner folded up the paper and slapped his knee with a brisk pleasure. “It’s your bus come to get you.”

Kigun stared at his grandfather skeptically.

Grandpa O’Conner glanced down quickly at his outfit. Same blue jeans bulging rather more at the thighs than he’d have liked, same boots from his father’s farm. No jelly stains on his plaid shirt. He’s leathery jacket was heavy and warm and adorned in the same, wafting tobacco perfume he always wore. He felt self-consciously at the brim of his hat, but no- it was still creased in the right places and doing its duty by hiding his receding hairline with its far cast shadow. Lastly, he ran his tongue across his teeth. He supposed they were yellow as always, and probably prominently so if they were perhaps catching the sunlight right- but no matter, Kigun had seen that before. There were no remnants of food in his teeth which had been the main concern. All in all, there was nothing the matter. “What?” he burst, crinkling his dark face into a sculpture of utter confusion.

“The bus comes every day, Poppy.”

“Oh.” Grandpa O’Conner laughed aloud in his relief. “Well, then-” and then a thought came to him. “Absolutely not, Kigun O’Conner,” he said abruptly, with renewed vigor.

Now Kigun was puzzled.

“Poppy?”

“Not on the weekends!” Grandpa O’Conner said proudly, beaming.

Kigun shrugged, unimpressed. He scooped up his backpack from where he’d dropped it and swung a strap over his right shoulder with the unconcerned grace that came from days of practice. Then he swiped his bangs from his eyes, studied the rate at which the bus was nearing, and began walking accordingly so that he wouldn’t have to wait to get on.

Grandpa O’Conner picked up the paper from the grass but kept his eyes averted. Bored, he let them roam over the sweep of the yard, picking out the toys Kigun had strewn in the most unlikely of places. For a second, he contemplated switching around the morning routine to allow for him to gather up all the toys and pile them up in Kigun’s room. Nah, he thought. He didn’t really want to move.

Kigun was nearly to the bus when he turned around. Shading his eyes with one careless hand thrown across his forehead, he gave a vague sort of wave in Grandpa O’Conner’s direction with the other hand. “Love you, Poppy.”

Grandpa O’Conner nearly choked on the response. His throat seemed suddenly laced with sour bile while, in contrast, sawdust seemed to seep into every crevice of his mouth, clotting between his teeth, building up like a plaster cast over his tongue. “I love you, too. You’re my boy,” he managed to choke out, before the bile-sawdust combination effectively muted him. How odd those words seemed, he thought. As if his mouth couldn’t really form that word correctly.

He shook his head to banish the thought. Nonsense. He was Joe O’Conner. He could say any old thing he liked.

He watched the bus pull away, and then continued watching until it had all but disappeared far off down the road, leaving a curl of black smoke slithering lazily in its wake. Then he unfurled the paper again and looked down at the article that had been buzzing through his brain relentlessly since he’d laid eyes on it. An iron bar closed around his windpipe, and his eyes blackened, until they were closed to the world. Until all he could see was a gaping chasm where his heart had resided. Even as he watched the chasm, the sight of it caused the hole to tear farther, widening. The iron bar pulled ever tighter. Eventually, though, the pressure subsided. He repositioned his fishing cap. Casually, he focused on the two black words that meant something within that sea of black words that meant nothing: Calvin O’Conner.

And there…. There were those other words! The awful words. But they no longer bothered him because there was no way they could be true. It was a lie. All a lie. And why should he waste any emotion on a lie? Why should he call someone he didn’t want to talk to just to ensure the paper was lying, when he knew it was lying without checking any other sources.

The police officer examining the dead victim’s body identified him as a Mr. Calvin Joseph O’Conner come from New York on leave from work. A photograph of a child with the name Kigun O’Conner written on the back, corresponded with an address that had been jotted down on loose-leaf bearing the same name, leads to the conclusion that Mr. O’Conner had either just been or was heading over to see his son or nephew at the time of death.

Grandpa O’Conner read it once more. So, maybe it was his son. Probably. It probably was, he decided. But that still didn’t mean he had to shed any tears over it.

He folded the paper meticulously into quarters and then folded it more until it resembled badly-done origami.

“Jesus Christ, Calvin,” he said, rising from his lawn chair. He looked over at the sun, already a brilliant ball of pulsating yellow-white. “You’re a real idiot, Cal,” he grumbled under his breath. “Never did any s*** right in your life till you knocked up that girl with my boy.” He squinted into the glaring light. “At least you got Kigun right, boy,” he murmured grudgingly. He paused. “You listening, Cal?” He looked around to make sure no living people were listening in. “Between us, Calvin,” he muttered as a slight flush crept up over his neck and face. “You got that one right, you know. You’re a good boy, I guess,” he admitted quietly. He blinked and a rather pained expression darted across his face. His nose curled and he spat as if something sour had infiltrated his mouth. “I guess you’re my boy, Cal,” he said quickly, darting glances every which way. “I guess.”

He started walking slowly home, dumping the paper into a crack between two bushes. “God damn gossip. Why can’t they just put in stuff about the garage sales in Portugal?” He adjusted his cap. “Maybe some god damn people want a know about those garage sales in Portugal, huh?”

He stomped up to the porch, nearly tearing the screen door off its hinges when he opened it. Grandma O’Conner was in the kitchen, squeezing lemons for lemonade.

“When the hell is Calvin going to send that check to supplement Kigun’s stuff?” Grandpa O’Conner asked the room at large. “Little son of a-” he closed his mouth quickly. “Gotta get his act together, don’t he, Helen?”

“I suppose,” she said. “Where’s your paper?”

“Dog gone paper boy forgot.”

“He’s never forgotten,” she said curiously, measuring out the sugar.

“Well, he’s forgot today. I’m going to bed,” he said, getting up from the table.

“You just sat,” she informed him. “And you never sleep in. I’ve got the bacon near done.”

“It’s never too late for a new beginning,” he grumbled. “Wake me up tomorrow for the Red Sox. And get rid of that bacon.” And

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.