All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

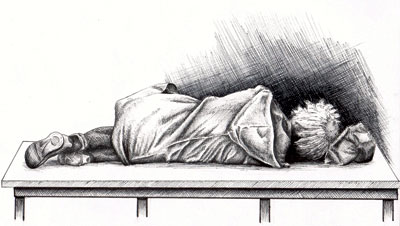

A Private Darkness MAG

When Grandpa died, he didn’t look like he was sleeping. He looked like he was dead.

It was Wednesday, August 16th. I remember because I circled it in purple Sharpie on my calendar. I don’t think Wednesdays are good days for dying. And purple was the wrong color to use. I should have used black. Red. Not purple.

I was lying in bed, about to fall asleep. It was humid that night – hot and humid. The whole world seemed like it had given up. Even the ceiling fan in my room was circling aimlessly, going through the motions.

The phone rang.

Grandpa’d been sick for weeks – well, years, really – and everyone knew he was going to die soon, knew in that “everyone knows” sort of way. There was a pause before Mom picked up the phone. It was 11 p.m. We all knew who was on the other end.

She said, “Okay.”

She said, “Thanks for calling.”

She said, “Take care.”

Then she hung up, and I heard her start to cry.

I sat up in bed, stared at my hands. They looked like they were glowing white in the dark. The room seemed like an oil painting, the walls fading into the floors fading into the windows and the night outside. The crying stopped. I guess that’s a good thing. You never feel more mature than when your parents cry. You never feel more helpless, either.

The hall light flicked on. An orange glow dribbled through the cracks in my closed door. I heard her walk down the stairs in slow, heavy steps.

I lay back down after a while. Stared at the ceiling. The fan kept moving.

They say – “they” being the people paid to think about these kinds of things – that there are infinite parallel universes in which everything that can happen has happened. In the days just before Grandpa died, wandering around hospital vending machines and watercolor landscapes, I’d hung on to that. There was a universe out there somewhere, buried under all of the nastier ones, where the hordes of nurses and doctors and blue-robed surgeons whispered about miracles as Grandpa clambered out of his bed, as he laughed it off and stretched out smelly, blue-veined legs.

Some alternate version of me was still laughing and happy and sleeping through the night. But the “Okay” and the “Thanks for calling” and the “Take care” cut that world off from me. I pictured it as a little slip of white paper snipped off by scissors, snatched by the wind out of my reach.

So he was dead. Cardiac arrest. The doctors told us he’d died in his sleep, nice and peaceful. Dad said it was a lucky way to go. Everyone repeated that comforting mantra. They were right. He’d had a long life. A happy life. Cardiac arrest. I guess it’s something to look forward to.

I was out of school for three days. Driving to the funeral, thinking about the funeral, going to the funeral, talking about the funeral, driving home from the funeral. We brought deviled eggs. Mom made them. She sprinkled spoonfuls of rusty paprika over the egg halves, coating the yellows and whites in dirty snow. I went back to school on a Tuesday. Weird day to go back to school. I told Mom that. She said to get out of the car.

In Spanish, the teacher was staring at the class’s potted plant. It was dying, had been dying, would continue to die until it was dead.

I asked her if she’d tried repotting it. She said she had. We stood there a while longer, her staring at the crispy little brown leaf points, me staring at the crispy little brown leaf points and trying to come up with something to say. I settled on “Too bad, isn’t it” and sat at my desk. She probably didn’t hear me. It was all right – I hadn’t ever really heard her, either.

That whole day was phony. Phony? No, phony’s not really the right word. You know what I mean. When you’re sitting, doing whatever – math problems, in my case – and your eyes are open. Wide open. Like you have two sets of eyelids, and this is the first time you’ve opened the second set. In a few decades, you’re going to be a skeleton. Every second, every passing second, is gone. You can’t get it back. Why the hell are you doing math?

It’s true, though, true in the way nothing else is. You’re going to die. Me, too. Sometimes I stand in a crowded place – Grand Central, say, or the middle of a city square – and sentence everyone to death. Study their faces, imagine what their skeletons look like under all that sinew, all that blood. That woman in the scarf and heels, clicking down the pavement. The man with the fluorescent coat, walking a dirty little terrier. The girl screaming at a boyfriend on her cell. Dead, dead, dead.

Have you ever looked at your hands? Really looked at them? There’s a skeleton a few millimeters below that smooth skin. A Halloween decoration. Dead, dead, dead.

I slipped out of gym class early that day and walked home. The world was in the awkward stage between fall and winter, when a couple leaves are still clinging onto the trees, holding off the snow. We live in a forest. The whole town is pretty much swarmed with trees. When we moved here, Mom spread her arms wide and talked about the forest in a hushed, magical voice, like saying the words too loudly would break them. I was seven. I’d grown up in Chicago. Trees were lonely little twigs sticking up out of sidewalks. I didn’t even know what a forest looked like.

We cremated him. Well, not “we.” Someone else stuck him into a fire, and he got burnt up. I asked Dad how much he thought the guy who stuck the corpses into the fire got paid. He said to be quiet and listen to the eulogy.

If you squinted at the floor in the reception room, it looked as though everyone was wearing the same shoes. Black blobs floating across the carpet. We all stood around and talked in low voices about what a wonderful life he had, what an absolutely wonderful life, goddammit. Couldn’t have it any better, goddammit. Not much point, is there? Black shoes and black suits, low voices pattering over the carpet. Wednesdays and purple ink and shoes. There’s no good way to eat a deviled egg.

Personally, I would’ve liked an open casket. I told Mom and she made a face. It would have made it real to see the body. The ash is nothing; the ash is ash. A blur in the air. Everyone should be able to touch the corpse, to pinch its cheeks, to feel its hair. To open and close its eyes. To understand. I didn’t tell Mom that part. I told my sister, though. She rolled her eyes and said there’s a name for people who want to touch corpses. Whatever.

It takes a while for me to walk home from school. It’s a mile and a half. That Tuesday, the forest didn’t look like what Mom had talked about in her hushed voice. The trees were thin and scraggly and bare. The mush of leaves spread across the dirt floor, shapeless. Around the trunks, thistles gathered, gossamer cages with those red poisonous berries clinging to their twigs like water droplets.

We’d learned about fruit flies in biology. Usually I don’t remember much from school, but that afternoon I thought a lot about fruit flies. It turns out they have no central nervous system. They – the scientists, I mean – did scans. Fruit fly MRIs. I like to think they built tiny little MRI machines for the tiny little fruit flies, that someone spent months hunched over a big desk with two toothpicks making microscopic arm restraints from sewing thread and specks of lint. That they gave the fruit flies mini hospital gowns and told them to just close their eyes and relax at the beep. They probably didn’t. They probably did something practical. But that’s what I like to think.

They saw little images of the little brains, and they learned fruit flies don’t have a central nervous system. They can’t feel pain. Nothing.

I saw a fruit fly today, actually. Swirling around my hand. I tried to brush it away, but my finger squished it; it made a brown dot that you could see if you squinted. I don’t think anyone bothered to squint, though. It’s interesting, that kind of moment. The fruit fly was buzzing around, thinking about – well, not thinking, exactly, but doing whatever fruit flies do – and then it was dead. No pain, no morphine drip. No tears. Just a tiny little end to one minuscule part of the world. Just a tiny little private darkness.

In front of my house, we have a Japanese maple. There was only one little clump of red leaves left, huddled together for warmth like the penguins in those British nature documentaries. When I stood at the front stoop, the sun blotted out the branches. For a second it shone through the last few leaves. They looked like a fluorescent haze, floating in the sky.

I unlocked the front door.

That night, I stood in the shower. I like the shower. In ninth grade, our English teacher spread her arms wide like Mom with her magic forest and told my class that showering is a rebirth. We were learning about themes of water and renewal in classical literature. Something like that, anyway. We all snickered. The rest of the year, we’d say things like “Getting pretty dirty. Tonight I better get reborn.”

But I like the shower. Maybe it is a rebirth. In one parallel universe, after this shower, I change my ways and study harder, go to Harvard, and end up president. It has to happen somewhere. Somewhere I step out of this shower and buy a guitar and write a famous song. Somewhere I step out of this shower and cure cancer. Somewhere I step out of this shower and go on to live a completely normal, happy life. Die of cardiac arrest.

I think I die in all the somewheres, actually.

And somewhere, I don’t go to Harvard or write a song or die of cardiac arrest. Somewhere I stand here in this shower and stare at the puddle around my feet, at the steam and the rushing water. Somewhere I close my eyes and my sigh is drowned out by the endless droplets. Somewhere I wish I was reborn, but instead I just stare at my feet, stare until the bathroom seems to vanish, until the tile turns to fog, until there’s nothing but the knobbly pair of feet. And somewhere I sit down on the cold tub floor, lean my head against the wall. Somewhere I’m one of those little droplets, falling and splashing and spiraling down down the drain.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 1 comment.

I wrote “A Private Darkness” in an attempt to identify the complicated emotions we all feel when we lose someone close to us. While it’s fictional (I’ve never been to Chicago, and Grandpa’s alive and well), I based it off my own experiences and thoughts. I hope that writing this will help others dealing with death – which is, let’s face it, all of us – and send the message that no one's alone.