All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

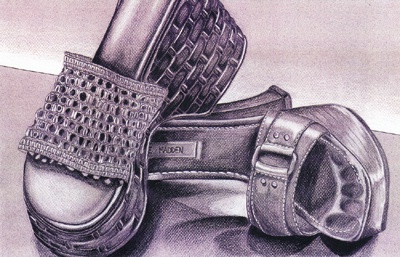

Fashion Forward

We’ve all been there: you walk into H&M and before you know it you´re standing in line holding three bags-worth of outfits that look curiously similar to those you saw walking down the runway just a month ago. But before letting yourself be seduced by the low price tags, consider the real cost of producing cheap clothes. Consider, for instance, the 1.5 million children under twelve working in the garment industry, or the 300 thousand garment workers in Mexico living on 50 cents an hour. This is a direct impact of our society’s demand for fast fashion and our frenzied rate of consumption.

Human rights controversy has historically plagued the industry. The persistence of this issue has been recently brought to light by the Rana Plaza collapse— 1134 dead and 2500 injured (most crippled) rightfully sparked outrage and initiated a global campaign for garment workers’ rights. Yet response from brands leaves a lot to be desired.

The clothing industry has seen exponential growth as a result of rapid industrialisation, population growth and globalisation (amplified by pervasive consumerism and competition to dominate the market), which created a drive for mass production at low costs regardless of the environmental and social implications. However, becoming a global commodity link comes at no small price.

Work in the textile plants has become synonymous with exploitation. Employees often endure unsafe, unsanitary working conditions; verbal, psychological and physical abuse (even sexual harassment); discrimination; work hours outside the legal limit; unpaid extra hours—and all “compensated” by meager wages that only cover 38% of what a family needs to survive. Moreover, trade unions are undermined, leaving workers voiceless. Yet given the rampant poverty and lack of opportunities in most leading clothes-manufacturing countries (such as Bangladesh, Thailand and Mexico), workers are willing to acquiesce. These conditions are mirrored in “sweatshops” around the world. Activist Julia Quiñonez points to a key aspect of the problem: ‘[Workers] are familiar with the labour side agreement [of NAFTA]. But, these parallel agreements don't force anybody to take responsibility’.

As consumers, we are the bedrock of the fashion industry. Having recognized this, global attempts to change the system have been based on buying power, such as initiatives that encourage boycotting or buying second-hand. These are band-aid solutions, and the negative repercussions are far-reaching. As Faustina Pereira, director of human rights at Bangladesh-based NGO BRAC, puts it, ‘we are dealing with a sector that directly touches the lives and livelihoods of millions of individuals and their families, and directly contributes to lifting them out of abject poverty’. Boycotting leaves these people without an income, damages the country’s economy, and ultimately has little effect on big brands. Choosing to buy at another company does not change the system that drives this need for mass production at minimum costs. And while recycling clothes does help slow down production rates, the second-hand clothes trade is often inefficiently managed and ends up flooding markets. This is detrimental to local industries and again workers are the ones to bear the brunt.

Brands must spearhead change, ensuring that workers in their supply chains are guaranteed decent livelihoods and working conditions that comply with international labour laws and regulations. However, as the primary benefactors of cheap clothes it is our responsibility to take action. Instead of leaving ethics to the grownups and proceeding to buy a $2.00 t-shirt made in Cambodia, do these things to change how you shop:

1. Buy ethical: Be sceptical. Ask questions, search a brand’s website, look for certifications (such as Fair Trade). Many brands use the ‘ethical’ label undeservedly, so DO YOUR RESEARCH!

2. Encourage companies: Buy from big brands that are taking steps towards improving working conditions; they are the ones with influence.

3. Pressure: Hold companies accountable for their factory conditions. Remember that acting ethically is not limited to your buying practices (we get it, fair trade clothes are expensive). Communicate with brands and tell them what you expect from them, sign petitions, send them e-mails, use social media.

4. Spread the word

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.

I wrote this piece after deciding that my love for fashion need not be at odds with my passion for defending human rights. I firmly believe that our choice should not be limited to spending $50 on a T-shirt or perpetuating the abuse of garment workers worldwide. Therefore, I hope that my writing will encourage readers to make smart decisions when shopping to bring change to the fashion industry.