All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

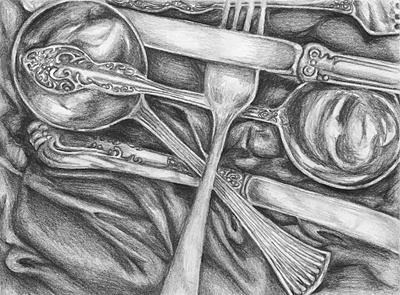

The Sausage Wars MAG

There is a war fought in my family. A terrible, beautiful thing. Every year around Christmas time, the battlefield is set. My grandparents act as surveyors, my mother and her sisters as peaceful interference, and my cousins and I as soldiers. We’ll wash our hands with soap and warm water until the skin on our knuckles is devoid of all natural moisture, like the shaved heads of military recruits. We wear the scent of soap like a uniform as we march into the small, cramped kitchen and crouch before a large, plastic bin filled with ground beef, as cold as the snow falling solemnly outside. With urging from our grandmother, our commander, we dig our fingers reluctantly into the squelching mass of raw meat before us. Hesitation quickly becomes vigor as we realize the competition between us. Our hands, then wrists are coated in a thick skin of cold, solidified fat as we dig into the meat, making rapid grabs at the spices thrown in by the adults.

The cold bites our skin and numbs our muscles, but we continue to mix, making sure to dive into the corners and make it all even. By now, we can’t feel our hands. Their disappearance aches at the ends of our forearms. Mercifully, as a possible act of God himself, our salvation appears. Potatoes, cut into bits, are tossed into a blender with gloriously hot water, stirred up into a grainy sauce, and dumped on top of our hands. The children warriors who survive this ordeal are the ones who bring most of that warm white sludge to their end of the bin and dig until it fills their fingernails and thaws their icy fingers. However, this satisfaction is short-lived, for it’s not long before the heat is drowned out by the undying cold of the meat around it, and these cousins are once again scrabbling in freezing pain, waiting for the next sweet plop of warmth, and hoping that we aren’t out of potatoes yet.

Though we’ve all got red nail marks in our hands and wrists, a consequence of our fierce competition, which sting a little as we dig into a field of spices on the surface of our meaty playspace, the worst is yet to come. The most wrecking weapon to the soldiers comes from our higher-ups themselves. My mother and her sisters all have various tasks set for themselves to speed up sausage production, but there will be one or two in charge of the children’s damnation in the form of fresh onions.

The onions are cut into small bits and dropped in like canisters of gas from above. Everyone in the kitchen is a victim, eyes stinging and tearing up, the moisture clinging to eyelashes offering little in the way of relief from the assault. Still, at least the adults, high up and on their feet, have clean wrists with which to rub their eyes, and can step out of the room for a moment of respite. The soldiers, covered from fingertip to forearm with meat and fat not only have nothing but unhelpful shoulders to rub our eyes with, but also are not allowed out of the room for the sake of preserving the cleanliness of the rugs and couches. For us, there is no respite or relief, but painful onions inches from our faces. We push them down beneath as much meat mass as we can before the next batch comes.

We continue to grind and cry into our own shoulders until the meat is fed through an old machine of dark metal, like some macabre torture instrument from an earlier, more morbid century. The squelching mass we have created is compressed and shaped by this tool with the loud screeching of metal rubbing against itself, and the mixture is let out into the thin skin of a cow intestine, supposedly cooked and sanitized.

At this point the kids are permitted to leave the room and scramble for one of the two bathrooms. It can take a good 20 minutes to feel even remotely clean, after a thorough rubdown with scalding water and as much soap as you can find. Anything less and the fat will cling to your skin and remain stuck between your fingers. Even after your hands are red and throbbing from the scrubbing and heat of sanitization, you will smell of meat for days, and your eyes will feel the phantom sting of onions.

This war and destruction is forgotten once the sausages are ready for consumption. The dish completes the Christmas buffet table, and nothing on this day is right without it. We veterans are resilient and easily satiated by the meal. We can forget our struggle – until we must survive it again next year.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.

This is entirely truthful, and though some metaphors are implemented, not an ounce of this piece is embellished. As I write and think about my words, I almost wish I had made some of this up, if only to spare myself the feeling of phantom fat and grease clinging to my fingers and rubbing off onto my keyboard.