All Nonfiction

- Bullying

- Books

- Academic

- Author Interviews

- Celebrity interviews

- College Articles

- College Essays

- Educator of the Year

- Heroes

- Interviews

- Memoir

- Personal Experience

- Sports

- Travel & Culture

All Opinions

- Bullying

- Current Events / Politics

- Discrimination

- Drugs / Alcohol / Smoking

- Entertainment / Celebrities

- Environment

- Love / Relationships

- Movies / Music / TV

- Pop Culture / Trends

- School / College

- Social Issues / Civics

- Spirituality / Religion

- Sports / Hobbies

All Hot Topics

- Bullying

- Community Service

- Environment

- Health

- Letters to the Editor

- Pride & Prejudice

- What Matters

- Back

Summer Guide

- Program Links

- Program Reviews

- Back

College Guide

- College Links

- College Reviews

- College Essays

- College Articles

- Back

Race in Schools and the Broader Spectrum: A Critical Analysis

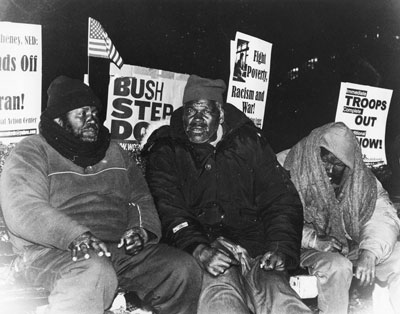

A mass of people slowly crawls around the corners of urban Atlanta with the ubiquitous call “Black Lives Matter” brazenly reverberating in the streets. At the other end of the spectrum, torches are lit in Charlottesville, Virginia, a response to a roar of White Nationalism and right-wing populism, as a new faction of the American political identity is forged from hate and xenophobic fears of the “other.” Both of these movements, despite their fundamental philosophical disagreements, stem from an elusive and relatively misunderstood component of our society: race. In the same breath, the race’s omnipotence both unifies vast groups of people under a common culture and creates chasmic power dynamics between the privileged and the underprivileged.

Race presents itself within every corner of our culture—between racial stereotyping, discrimination and the intersection of class and race, it is an intrinsic element of all interactions from the micro to macro level. However, there is an underlying disconnect between what we perceive race to be and what it actually is. In contemporary scholarship, race is regarded as a social construct, a symbolic identity only defined by the society that circumscribes it—it is not qualified as a physical or biological characteristic. This highlights the failure of many attempts to differentiate races by broad-brushed physical and behavioral traits when there is no biological precedent to tether these perceived differences to. This is best exemplified by the advent of social darwinism, an imperialistic ideal held by white Europeans that applied Darwinian theories of natural selection to humans and racial classifications, typically coming to the conclusion that the mental capabilities of colonial indigenes were less than that of the white race. An insidious manifestation of this logical fallacy in the modern age has become the recent revival of “race science,” as a small group of IQ scientists and anthropologists try to prove that certain races are inherently more intelligent than others. This elemental misunderstanding is the root of racial otherization and tribalism, a gateway to racism and discrimination. Many scholars and philosophers have attempted to understand and define race’s relation to society and culture, the most developed of which has become critical race theory.

Critical race theory is a branch of critical literature and academic studies that focuses on race and its relation to people’s position in the world. In this theory, many prominent authors focus on the relations between the American government and its structural antagonisms toward specific groups of people. Focusing on the African American ontology, scholars traditionally consider two camps of broad philosophies: Afro-Pessimism and Afro-Optimism.

While both theories deal with the African American’s relationship to society, the ontological position of Black bodies in America is important to understand. Ontology is a state of being; just as a teacher’s position in the classroom to students, critical race theory proposes race as a feature that defines who you are and what you can do in life. Using ontology in combination with race, theorists believe that race places people in certain categories that affect how the world sees them.

Afro-Pessimists believe that it is impossible for African Americans to orient themselves effectively towards the government or society in general. Historically, the U.S. has disenfranchised African Americans, exemplified by structural disadvantages and inherent societal discrimination, and has been built up on a foundation of anti-blackness and slavery. According to Frank B. Wilderson III, an eminent philosopher at the forefront of Afro-Pessimist thought, the vestiges of slavery remain in the ontology of black bodies, so much so that it is an intrinsic element of blackness.

"Slave-ness has consumed African-ness and Blackness to make it impossible to dissect and divide blackness from slave-ness. …When we recognize that we cannot be recognized and move on with that, [Nat Turner, Harriet Tubman, Black Liberation Army, etc.] the response to those moments is so overwhelmingly violent that it doesn’t seek to end the conflict. It seeks to crush us to the point that nobody gets that idea in their mind again,” said Wilderson III.

There are always going to be winners and losers in society, and because of the government’s institutionally antipathetic propensities, those losers have frequently been African Americans. In the eyes of Pessimism, there is no future for the Black body within the world’s current structure. Theorists advocate for different futures, but perhaps one of the most radical alternatives is the end of civil society itself.

“Two hundred years ago, when the slaves in Haiti rose up, they … burned everything because everything was against them. Everything was against the slaves, the entire order that it was their lot to follow, the entire order in which they were positioned as worse than senseless things, every plantation, everything,” said Afro-Pessimist scholar Anthony Paul Farley.

The dichotomy between Afro-Pessimism and Afro-Optimism is most simply explained by the interactions between two immensely influential leaders in the Civil Rights Movement, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr. While Malcolm X advocated for violent resistance against white aggression as the only way to break down systemic racism, MLK Jr. saw a world that was only getting better for African Americans.

"We've broken loose from...slavery and we have moved through the wilderness of legal segregation. Now we stand on the border of the promised land of integration." said MLK Jr. in his famous I Have a Dream speech.

Malcolm X however, is on the polar opposite of the spectrum. Following the ideals behind Afro-Pessimism, he called for a more radical movement against institutions like the police, especially using violent means.

Critics of critical race theory point to an emergence of a perceived black-white binary in race, one they see perpetuated by the philosophies and authors of Afro-Optimism and Afro-Pessimism. The black-white binary is a viewpoint defined by seeing race, especially in America, as two sides of a coin, only consisting of the Caucasian and African American experience. Race instead is a spectrum spanning different cultures, ethnicities and societies—to ignore that is to ignore the voices of those falling on the periphery of this binary.

“I think [the black-white binary] is extremely toxic to experiences of people who aren't included. Like growing up I actually thought I was white. Just because that's what I understood as race, its either you’re black or white. I assumed that I could be white and Chinese, which just comes to show how race itself is very diverse or a lot more complex than what is discussed today,” said senior Jason Ling.

The implicit eviction of races outside of the black-white binary from the discourse surrounding race relations directly impacts the largest minority population at my high school, Asian Americans. This cultural neglect has translated to a patronizing, docile image of Asian Americans throughout the history of the United States and an air of ignorance toward discrimination against Asian Americans.

“Our voices are almost never listened to. We’re stereotyped as quiet and obedient, we never express our complaints, we just work through it,” said Ling.

From this portrayal of Asian Americans stems an even larger and more harmful generalization: that Asian Americans are the “model minority” of America's contemporary ethnic and racial landscape due to their unparalleled economic prosperity and educational eminence. Largely discounted as a myth, those who perpetuate this concept of the model minority often homogenize a wildly diverse racial group, with ethnicities spanning from the Middle East to East Asia. The image of an Asian American for many, however, singularly remains a strawman depiction of an East Asian student hunched over and fervently toiling over math problems, despite abyssal socioeconomic disparities between Asian groups. This monolithic portrayal of Asian Americans has not only submerged them under an inescapable and largely inaccurate stereotype; the model minority is also often employed as a wedge between racial minorities, especially African Americans, as the success of Asian Americans and “failure” of other races are depicted to be not results of inequality, racism and incomparable migrational conditions, but of inherent laziness and indolence among African Americans and other racial groups. This pardons the privileged in our society from their responsibility to confront the root cause of African American socioeconomic plight because, according to the logic of powerful elites, if Asians can succeed, why can’t African Americans?

“It’s because the U.S. has practiced these immigration tactics where they’re fishing the best out of Asia, putting them on this pedestal in America and then pointing at other minorities who are either already here or who are migrating in the same way, saying if you’re not this expectation that we’ve hand-groomed, then you are not valid in our country. That’s what the myth is,” said Ling.

Beyond my high school, race plays a distinct role in schools, serving as a haunting reminder of race’s historically inextricable entanglement with class and socioeconomic welfare. Take Banneker High School, located in College Park, Atlanta.

“It was predominantly a black school, and in that case you have parents who were working multiple jobs or going to school for higher education for the first time at that time. So you had students who were left to their own devices after school. There was also a large population of kids who were in group homes, who had no strong family system for support. That impacted a student’s ability to focus on school, because it was more about basic needs and survival,” said former Banneker English teacher Mrs. Clowe.

At Banneker, 100% of the student population is economically disadvantaged and on the national free lunch program, and 96% of the student population is African American. When compared to the pillar of affluence that is my high school, boasting a significantly lower minority population and rate of economically disadvantaged students, our society’s mendacious guise of racial egalitarianism is thrown into question. Numerous institutional forces—urban housing and the governmental subsidization of suburbs on the contingency that homes would not be sold to non-whites—have contributed to these towering wealth discrepancies between classes and races, but we as culture seem to accept these purposefully discriminatory policies as a sort of natural law. For many of us, the north side of Fulton County is rich and the south side is poor; that is how it is and that’s how it will always be. The day we begin to question our inherent assumptions and these robust structures of racial inequality that are steadily fortifying in our society is the day we pave our way towards equality.

Similar Articles

JOIN THE DISCUSSION

This article has 0 comments.